David's Mystery

One thing that always intrigues me with First and Second Samuel is how they hint at ulterior motives for many of David’s actions which consistently become pointed out in the Editor’s notes by Herbert Marks. The mystery behind David’s character is also an integral part of Robert Alter’s analysis of the Bible in his “Characterization and the Art of Reticence” in which he describes the importance of the Bible’s sparse detail, which has been emphasized in other analyses of the Bible, though Alter specifically looks to describe such sparse language as an intentional decision that instead of being omnipresent is selectively chosen for specific purposes.

The first noteworthy mention of David’s mysterious character is his loyalty to Saul even after Saul seeks to kill him. We get many outward expressions of David’s loyalty to Saul, and when David has multiple chances to kill Saul but does not take them, he makes a rather big deal of it, speaking at length about his righteousness in the face of Saul’s hatred. Specifically, when David spares Saul at the cave in En-gedi, he explains his actions to his servants, proclaiming that “The Lord forbid that I should do this thing unto my master, the Lord’s anointed, to stretch forth my mine hand against him, seeing he is the anointed of the Lord” (First Samuel 24:6). Here, David very much emphasizes his relationship with God, twice mentioning his inability to kill Saul because it would seemingly betray The Lord Himself as Saul is His “anointed”. A second time, David has the opportunity to kill Saul on the hill of Hachilah in a story that very much mirrors the first one. Interestingly enough, despite being loyal to Saul and vowing not to kill him in En-gedi, he goes through the trouble to sneak into Saul’s camp and even specifically asks for someone to go into the camp with him. With his experience in En-gedi, why would David want to bring one of his men into Saul’s camp, knowing full well that they want to kill Saul, if not to make a very public point out of his unwillingness to “stretch forth his hand against the Lord’s anointed” while explaining that “The Lord forbid that I should stretch forth mine hand against the Lord’s anointed” (First Samuel 26:9-11). Again, David says twice that he will not kill Saul because it would supposedly go against God’s will, and he makes sure that there is Abishai with him to witness his holy restraint. What makes this scene an incredibly blatant attempt to demonstrate his mercy in contrast to Saul’s relentless need to murder him is how he calls to Abner to reveal that he has taken the “king’s spear” and “cruse of water” to demonstrate that he was in the king’s camp but did not kill him (First Samuel 26:16). Just like how David flaunts Saul’s torn skirt in En-gedi, David makes a public affair out of his righteousness in not killing Saul. Throughout this whole series of events, we get very little detail about how David actually feels as he grants his mercy time after time, standing in stark contrast to how much he outwardly emphasizes his mercy and need to follow God’s will, hinting at a potential political motive to demonstrate himself as a more worthy individual than Saul to be God’s anointed king.

On the other hand, Robert Alter analyzes David’s mysterious character mainly within the context of his relationship to Saul’s daughter Michal. Perhaps most interesting about this pair is that Michal is explicitly said to “love” David twice, what Alter explains is “the only instance in all Biblical narrative in which we are explicitly told that a woman loves a man”, but David’s own feelings toward Michal remain ambiguous. Instead, what we are told is that “David was pleased by the thing, to become the king’s son-in-law” (Alter 2071-2073). Again, instead of being entirely sparse in its description of characters, the Bible is oddly specific in mentioning that Michal loves David twice, an explicit detail used nowhere else in the Bible, but it rather plainly states that David is happy about the arrangement seemingly only because it means he would be connected by blood to the king. As a result, even early on, David is implicitly portrayed as being very politically ambitious as the only details we get into his actions reveal highly political motives. Looking on David’s narrative arc as a whole, I see very little explicit depth in his character at all. From the beginning, when he faces Goliath, he seems like a hotheaded youth whose only concern is to prove the grace of God by defeating a non-believing Philistine. We see no fear or emotion from David, only action as he rushes to kill Goliath. His later victories in battle for Israel also reveal very little about his character other than how he seemingly is blessed with the grace of God allowing him to be so successful. He becomes incredibly loyal to Saul, seeking to become the king’s son-in-law through marriage and refusing to kill Saul even when Saul decides to start hunting him down. When Saul eventually dies, David very publicly grieves Saul’s death and vows not to end Saul’s line which he also makes a public display of honoring later on. By the time that David rises to the throne, there seems to be little more to his character than the grace of God and loyalty to Saul, both of which help him gain proximity to the holy position of The Lord’s anointed king over Israel.

Even during David’s fall from grace, we get frighteningly little insight into his personal character. Perhaps the most human thing he does in the Bible, falling in love with the beautiful Bathsheba, gives us only a brief glimpse into David’s true character. He makes the very human mistake of laying with the wrong person and scrambles to hide evidence of the act through an elaborate plan with Uriah the Hittite that ultimately kills Uriah. All we learn here is that even David makes bad decisions, and like any other reasonable person, does not want his mistakes to become too publicly known. Additionally, as Alter details, we get an interesting characterization of David later on as he spares no expense begging God for the life of his firstborn son by Bathsheba, but immediately after learning of his son’s death, returns to life as normal stating that his son “will not come back” no matter what he does (Alter 2080). Out of this same passage we get a surprising straightforward explanation from David stating, “when the child was still alive I fasted and wept, for I thought, ‘Who knows, perhaps the Lord will take pity on me and the child will live.’ But now that he is dead, why should I fast? Can I bring him back again?”. The rhetorical questions within David’s actual thought processes reveal an inside look on David that we have never before received, in an argumentative style that I personally very much relate to, but at the same time, it reaffirms the very logical and contemplative outward actions by David. He only begs for his child's life as a show to God and the people around him of his faith, but once such a show no longer has a purpose, he immediately throws out the fanfare of his grief. It seems an intentional decision to tease the reader with a look into David’s personal life just to draw David back into the mysterious shroud of his true intentions.

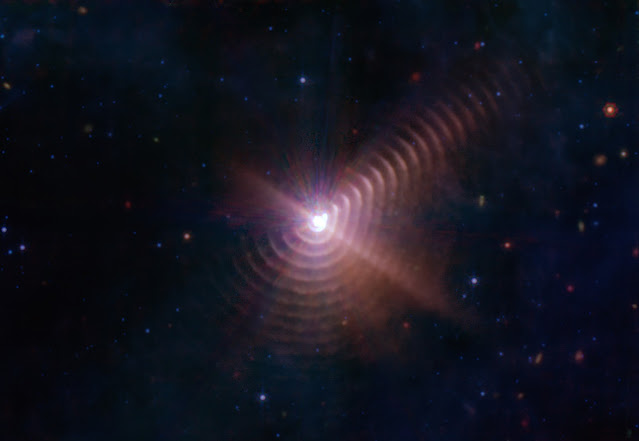

I believe this story has an interesting connection to the most recent picture from JWST above depicting Wolf-Rayet 140, an incredibly rare star pair, as the image reminded me of the mystery surrounding David. The star pair is unique because they orbit each other in a way that draws them close enough for their stellar winds to collide about every 8 years, creating rings of dust from gas that emanate outward from the star pair like tree rings. To me, the rings of dust symbolize the repetitive mentions of David’s outward actions that characterize him solely within the context of his loyalty to God and Saul, both of which help him gain the throne of Israel. However, at the center of those rings of dust lie David’s true intentions, which may or may not be political in nature, but are hidden behind a constant stream of outward actions that conceal his emotions and motives. Whether or not this analogy holds up to rigorous analysis, I still think the image above is a breathtaking show of the amazing things this universe has hidden everywhere while the Book of Samuel is a similarly interesting display of literary characterization through the intentional use and lack of description.

Comments

Post a Comment